Leonard Bernstein: The Total Musician

A Personal Remembrance

by Jeffrey Dane

(Page 5)

Bernstein's Children

Though the Bernstein children were living elsewhere, they retained the 8-room apartment and stayed there on occasion. I was told it also served as a headquarters for the various enterprises in which the Bernstein children are involved -- Alas, this has changed, more about which, presently.

Soon there were several dozen people present. I shook hands and spoke with Jamie Bernstein Thomas, Lenny's daughter and his eldest child; and I saw (but didn't have a chance to speak with) his sister, Shirley, who has since passed away. I was later told that Bernstein's youngest child, Nina, was also there briefly (and that she had even arranged the catering for the event!), but alas I didn't get to meet her.

I had met Alexander Bernstein in mid-January after a seminar at the Museum of Television and Radio in Manhattan, and tonight I had the pleasure of speaking with him again during the course of the evening. At one point I asked him if it would be possible for me to see his father's studio, even if only briefly, and I added that if he'd allow it, it would frankly mean a great deal to me. "I know it would, but I just can't," he replied, with a clearly sincere regret in his voice. Well, there was certainly no harm done; I told him I understood entirely, which was true; that simply to have the opportunity to be here on this evening was, for me, a privilege in itself (also true); and there was no question that what I was seeing and experiencing here on this evening was well worth the visit. I soon learned that the maestro's own private studio was isolated on one of the upper floors -- very appropriate positioning, since even though he was 5'8" tall (by coincidence, my own height), he towered above most of us musically. I also learned that the studio was being prepared for the organization of the Leonard Bernstein archives. So near, and yet so far. . .

To have visited this apartment remains a personal experience which can be described only as unique, just as my having heard Bach's music performed in his own Thomaskirche in Leipzig remains perhaps the most moving musical experience of my life. The feeling of euphoria in both cases was as intense as my sentiment of sorrow when, in June 1997, I had the gut-wrenching experience of passing the Dakota and seeing workmen gutting the apartment: it had been sold by the Bernstein family. It was of course their decision to do so, and our decisions are justified as long as they are honest and satisfy us. Nevertheless, the personal sadness I felt defies description.

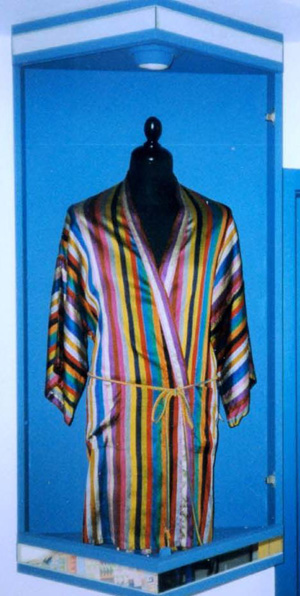

The AuctionA suit of Bach's clothes is exhibited at the Bach Museum in Leipzig. Locks of Beethoven's hair are kept in glass showcases in two Viennese museums. Three of Brahms' inkwells are displayed in as many locations in Austria -- and now there is a fourth "B" perpetuated as a result of the Sotheby's benefit auction late in 1997 of articles that belonged to Leonard Bernstein.

This auction prompted a paradoxical sadness and excitement simultaneously. Behind the otherwise ordinary objects of no intrinsic value there are the revealing stories about those who used them. It's because of their personal association that these objects are so revered. The items may be inanimate, but they're very much alive with the history of their own usage.

Even the smaller objects that graced the family's Dakota apartment had significance for someone, including myself. Having been not just owned but actually used by the Maestro himself, they had a tangible connection to him. Most significant for me was Lot #209, described in the Sotheby auction catalog as, "Multicolor striped silk short robe with braided cord sash. Worn by the Maestro to greet well-wishers after concerts." Though not pictured in the catalog, from its description I knew immediately and exactly what the item was: the very robe

Lenny is wearing in the photo, taken by my wife, of the two of us.A new vocabulary would have to be invented to describe how keenly disappointed I was in not acquiring it, and I freely acknowledge I envy the one who did -- even before I learned who she was. Imprudent folks may focus on what they lack, while others are grateful to recognize and appreciate what they have. The robe ultimately went to a very fitting recipient: a young student of conducting in Germany named Anke Weinert, with whom I soon had the pleasure of corresponding. I hope to some day meet her.

One incident in particular stands out more than others in my memory of that evening at Bernstein's Dakota apartment. -- On the piano's music rack were three scores: by Chopin (the Mazurkas), Ravel (the piano transcription of Le Tombeau de Couperin), and a volume of Bernstein's own music, the Bernstein Songbook, marked on the front cover in red pencil, "Corrected." I glanced through this printed edition and noticed red-pencil markings and corrections to this score -- markings in what appeared to be Bernstein's own note-hand for the notation alterations, and in his own letter-hand for the marginal prose remarks. To the left of the music rack was a holder with various ordinary, "garden variety" pencils -- including a red one. . . I must admit to the thought of merely placing this simple red pencil in my pocket, but I fought and overcame the temptation: I decided just to hold the pencil in my hand momentarily, not to "take" it forever, and I returned it to its holder. Yes, it would have been a cherished and very personal keepsake for me and would have been missed by no-one, but it remained in its receptacle. We're responsible only for our actions, not for our thoughts -- and certainly not for our dreams. So far, and yet so near. . .

Final ThoughtsI don't pretend to have been "a close personal friend" of Leonard Bernstein (though I do wish I had been). My initial view of him was that of a then-young student, a schooled musician and trained observer, who admired him tremendously and who was fortunate enough to know him even as an acquaintance. We were not intimate friends in the traditional sense, yet we were not total strangers, either. This peripheral view has a perspective others may not: we can't see the picture if we're inside the frame. There are of course many people who knew him even in this casual way, but it's very pleasing -- it's even a source of pride -- for me to know that I am one of them. He seemed to accomplish more in a year than most of us do in our entire individual lifetimes. He may have been, essentially, moments in my personal weather -- but they were moments that had a profound effect on the climate of my life.

Though he's no longer here, Leonard Bernstein is still,

and will forever remain, with us.

All photos with this article are from the author's personal collection.

About the Author

Jeffrey Dane was a researcher, historian, and author whose work appears in publications in several countries and in various languages. He has been a contributor to several books, including Leonard Bernstein -- A Life by Meryle Secrest.

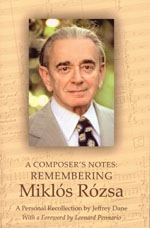

His book, A Composer's Notes: Remembering Miklos Rozsa

was published by iUniverse for the 2007 Rozsa centenary.

A Composer's Notes:

Remembering Mikos Rozsa

A Personal Recollection by Jeffrey Dane

See also this tribute by Jeffry Dane:

Film in Focus No. 4:

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS and Elmer Bernstein

This CD received a Sammy Film Music Award for

Best Golden Age Film Score -- click here

Return to the first page of

Leoanrd Bernstein: The Total Musician

Other Composer Tributes on the AMP website

Please help support the educational mission of the

© 2008-2024 PineTree Productions. All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)